On the morning of Thursday, May 23, 1889, David W. Vandeveer woke to find his Newfoundland dog, Rebel, dead. Nine other dogs in Stanford, Kentucky, would be found “sleeping the sleep that knows no waking” that day.[1] Who, or what, had killed ten dogs in this small town?

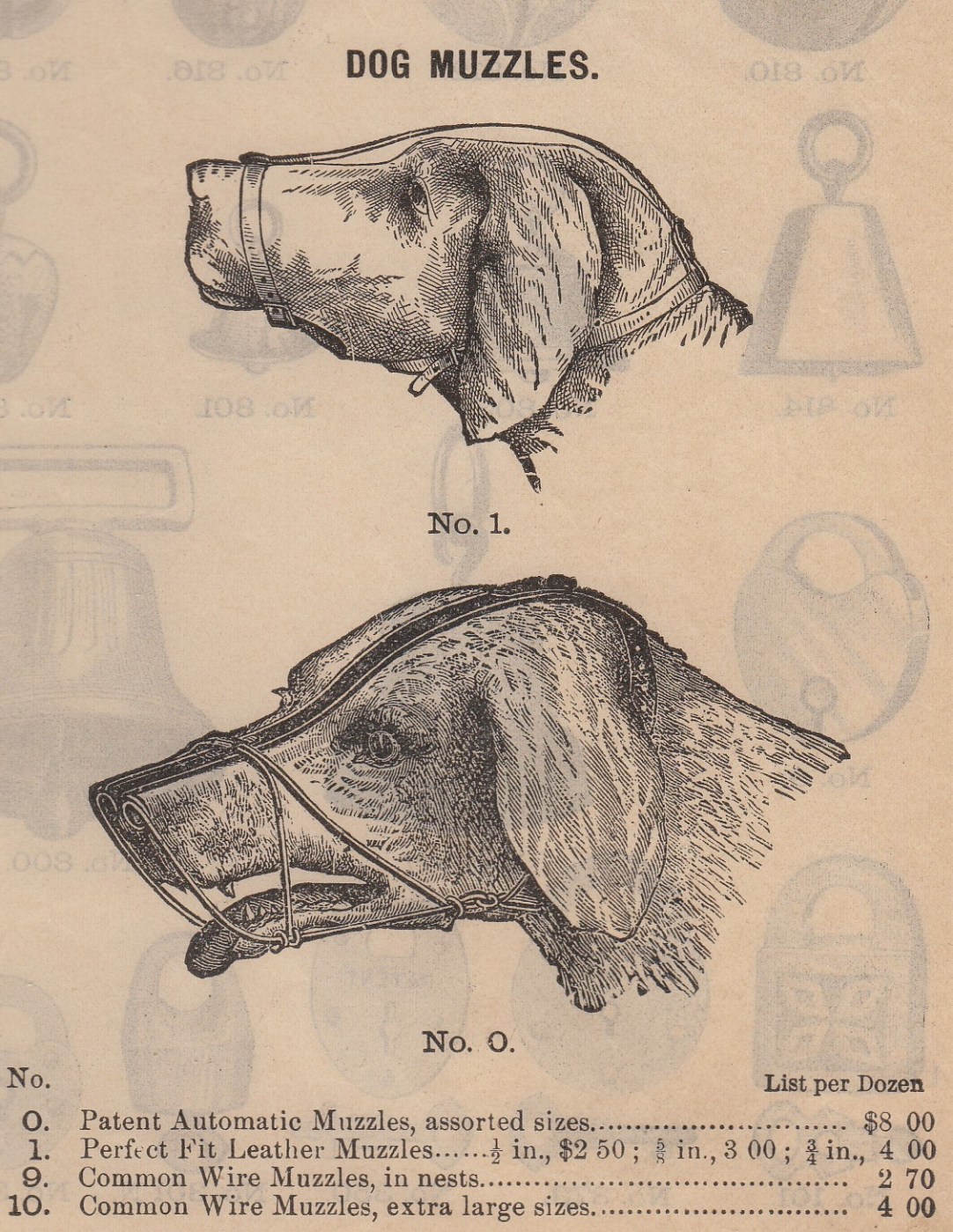

Stanford’s newspaper, the Interior Journal, reported on the abundance of doggy deaths, mysteriously asserting that while some “say the frost killed [them]… the general impression is that a ‘button’ did the work.” The author goes on to state, “It is muzzle or death now and we are glad to know that the owners seem to prefer the latter.” These remarks raised many questions in this modern-day reader. Wouldn’t late May in central Kentucky be an odd time for frost? What do they mean by a “button”? Why would a dog owner prefer their pet’s death to a muzzle? The story is by no means significant in the grand scheme of my family’s genealogy, but I could not help but dig a little deeper.

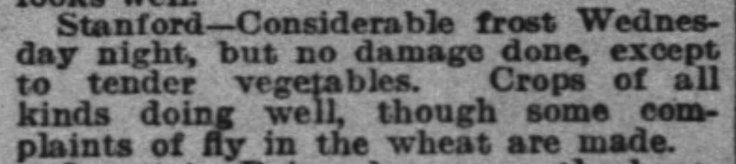

While the website for the National Weather Service does not have records for Stanford, the town is just over 35 miles southwest of Lexington. The latest spring frost on record for Lexington occurred on May 27, 1961, a month later than the average date of April 27th.[2] While reviewing these frost and freeze schedules, a fellow genealogist located a weather report from the Monday, May 27, 1889 edition of Louisville’s Courier-Journal newspaper:

So, there we have it – there was a “considerable,” though much later than average, spring frost on the evening of Rebel’s death. Perhaps this frost damaged more than vegetables that night?

However, is seems the town consensus was that a “button” was the cause of the dogs’ demise. The word “button” is defined as not only the common clothing fastener, but also “any of various parts or growths of a plant or of an animal: such as (1) bud, (2) an immature whole mushroom” or even “the terminal segment of a rattlesnake’s rattle.”[4] Perhaps the dogs had, en masse, ingested poisonous plants? Or a remarkably lethal rattler slithered through town, exacting revenge on its canine competitors? The Kentucky Department of Fish and Wildlife Resources reports that two species of venomous rattlesnakes inhabit the Bluegrass state – the timber and the pygmy rattlesnakes, though the latter only occupies Calloway, Lyon, and Trigg counties (David and Rebel lived in Lincoln county). The timber rattlesnake is the state’s largest venomous snake, growing up to five feet in length. Despite their size, timber rattlesnakes normally feed on rodents and squirrels, so it seems unlikely that one would choose fight over flight when confronted with a lumbering Newfie and nine friends.[5]

No, it doesn’t seem that the “button” in question was a plant or a snake that happened upon ten separate dogs. On the recommendation of another researcher, I began searching newspapers in the Stanford area for other mentions of “buttons,” especially in reference to dogs. A few days after Rebel’s unfortunate passing, the Interior Journal reported the following:

On May 24, the Kentucky Advocate of nearby Danville, reported:

A quick search of nearby papers turned up many reports of “mad dogs” and much fear of “hydrophobia” – an outdated term for rabies, which can cause difficulty swallowing and thus a “fear” of water in its advanced stages.[8] An Indiana man with questionable veterinary knowledge was quoted in the May 3, 1889 edition of the Interior Journal, advising that “All dogs have a small white worm at the root of the tongue on the underside, and running lengthwise. This worm is the source of all hydrophobia; take it out and your dog is safe.”[9]

Fortunately for the people and pets of Stanford, Louis Pasteur was already hard at work on a vaccine against the disease (which is caused by a virus, rather than a worm), and had successfully treated his first human patient four years earlier.[10] However, the vaccine may not have been well-known or readily accessible in Stanford, Kentucky at that time. If your neighbor’s unruly dog may be carrying a disease that is almost always fatal once symptoms arise, it is more understandable that some may be drawn to the sneaky distribution of poisoned “buttons,” and the newspaper writer may have preferred the certainty of the dogs’ deaths to potentially fallible muzzles.[11] Sadly for Rebel, our relative failed to procure a vaccine or a muzzle, and his large “nanny dog” seems to have fallen prey to the fears of his neighbors.

That, or Stanford had a serious rattlesnake problem.

How Are We Related?

Sources

[1] “Rebel,“ Interior Journal (Stanford, Kentucky), 24 May 1889, print edition, archived (https://www.newspapers.com/image/223180116/ : accessed 4 October 2018), column 2; citing print edition, p. 5.

[2] “Frost and Freeze Information for Lexington, Kentucky,” National Weather Service (https://www.weather.gov/lmk/lexington_freeze_info : accessed 4 October 2018).

[3] “Facts For The Farmers,” The Courier-Journal (Louisville, Kentucky), 27 May 1889, print edition, archived (https://www.newspapers.com/newspage/32445233/ : accessed 5 October 2018), column 6; citing print edition, p. 6.

[4] “Button,” Merriam-Webster (https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/button : accessed 5 October 2018).

[5] Moore, Bill, compiler. Kentucky Snakes. Kentucky Department of Fish and Wildlife Resources, April 2002. Digital images (https://fw.ky.gov/Wildlife/Documents/kysnakebook.pdf : accessed 5 October 2018).

[6] “City and Vicinity,” Interior Journal (Stanford, Kentucky), 28 May 1889, print edition, archived (https://www.newspapers.com/image/223180129/ : accessed 5 October 2018), column 2; citing print edition, p. 3.

[7] “Danville and Vicinity,” Interior Journal (Stanford, Kentucky), 24 May 1889, print edition, archived (https://www.newspapers.com/image/237402254/ : accessed 5 October 2018), column 3; citing print edition, p. 3.

[8] “Medical Definition of Hydrophobia,” MedicineNet, 13 May 2016 (https://www.medicinenet.com/phobias/article.htm : accessed 5 October 2018).

[9] “Prevention of Hydrophobia,” Interior Journal (Stanford, Kentucky), 3 May 1889, print edition, archived (https://www.newspapers.com/image/71294479/ : accessed 5 October 2018), column 1; citing print edition, p. 9.

[10] Offord, Catherine. “The Rabies Vaccine Backstory,” TheScientist, 1 June 2016 (https://www.the-scientist.com/foundations/the-rabies-vaccine-backstory-33441 : accessed 5 October 2018).

[11] “Rabies,” World Health Organization, 13 September 2018 (http://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/rabies : accessed 5 October 2018).

Leave a comment