Hugh Lonney was born on March 17, 1794 in Enniskillen, County Fermanagh, Northern Ireland [10]. Enniskillen, from the Irish Inis Ceithleann, translates to “Island of Ceithleann”, a mythological goddess. The story goes that Ceithleann had been injured in a battle, and attempted to swim across the River Erne to escape her enemies, but drowned before reaching the island [3]. By 1820, Hugh’s own travels had far exceeded those of his town’s namesake – he had successfully crossed the Atlantic Ocean with his mother, Catherine, and his wife, Catherine “Kitty” (née Warmsley) [10, 11]. I am unsure what prompted the Lonneys to leave their home – the Great Hunger, or the Irish Famine, would not strike his country until the 1840s. The majority of Irish immigrants to America by this time had been artisans or professionals who were able to quickly assimilate and prosper in the United States. The travelers wrote home often, telling of luxuries and comforts of which the average Irish family could only dream [7, 8]. Fittingly, Hugh and his family had chosen to settle in Lexington, Kentucky, known at the time as the “Athens of the West” [11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16].

Hugh worked as a grocer at the corner of Broadway and High Street in downtown Lexington [14, 15, 19, 20]. He and his wife Kitty welcomed five daughters and three sons into their family in just over a decade. In order of birth, the children were Kitty, Mary, Martha Ann, Margery Jane, Thomas Jefferson, Catherine, William, and Hugh, Jr. [10, 11, 12] Amidst these joyful times, the plague of cholera had begun its insidious creep across the budding nation.

From its original reservoir in the Ganges Delta of India, food and water contaminated with the bacterium Vibrio cholerae caused severe, watery diarrhea that could kill within hours if untreated. Transmission of the highly virulent illness is closely linked to inadequate access to clean water and sanitation facilities, and is more common in urban slums in modern times [1]. The germ theory of disease had yet to be widely accepted at Hugh Lonney’s time. It was more commonly accepted that epidemic illnesses were caused by “miasma” – noxious air polluted by foul-scented, rotting organic matter [4]. So perhaps rather than calling him a germaphobe, it may be more historically appropriate to label our Hugh a “miasmaphobe.” Famed Kentucky author, James Lane Allen, mentions our fastidious forefather in his 1891 short story, King Solomon of Kentucky:

“Down on Water Street, near where stands a railway station, Hugh Lonney, urging that the fear of cholera was not the only incentive to cleanliness, had just fitted up a sumptuous bath-house, where cold and shower baths might be had at twelve and a half cents each ($3.58 in 2017), or hot ones at three for half a dollar ($13.79 in 2017).” [5, 6, 16]

The youngest Lonney, Hugh Jr., was just seven months old when cholera finally arrived in Lexington on the first of June, 1833. In less than ten days, fifteen hundred citizens of the Athens of the West were dead. Author George Washington Ranck wrote:

“The streets were silent and deserted by everything but horses and dead-carts… Business houses were closed, factories were stopped, and men passed their most intimate friends in silence and afar off, staring like lunatics, for fear the contagion was upon them. The dead could not be buried fast enough, nor could coffins be had to meet half the demand. Many of the victims were consigned to trunks and boxes, or wrapped in the bedclothes upon which they had just expired, placed in carts, and hurried off for burial without a prayer being said and no attendant but the driver. The grave-yards were choked. Coffined and uncoffined dead were laid at the gates in confused heaps to wait their turn to be deposited in the long, shallow trenches, which were hastily dug for the necessities of the occasion.” [23]

Despite his best efforts to protect his fellow townspeople from the disease, Hugh would lose both his mother and his wife to cholera within a few months of its arrival [2]. However, by a stroke of luck or successful sanitary precautions, none of Hugh and Kitty’s children succumbed to the epidemic [10].

The public health crisis eventually waned, and Hugh remarried in May 1837. His new wife (our ancestor), Nancy Harris, was nearly twenty-five years younger than her husband – just three months older than his daughter Mary [10, 18]. Hugh and Nancy had seven children in the decade after their nuptials. In birth order, their children were Thomas Jefferson (yes, he also had a son named Thomas Jefferson with his first wife, and yes, the first one was still alive when the second one was born), Edward Harris (named for his maternal grandfather), James Samuel, Elizabeth, twins Hettie Ann and Jonathan Polk, and Rebecca [10, 13, 14, 15].

Hugh was once again predeceased by his other half, when 39-year-old Nancy fell victim to consumption (now known as tuberculosis) in April 1858 [18, 20, 21]. After suffering a few years of poor health, Hugh died suddenly and unexpectedly in his chair on January 18, 1863, at age sixty-eight [17, 19, 22]. He and Nancy were buried in the Lexington Cemetery, which, somewhat poignantly, had been established in 1849 to bury the victims of a subsequent cholera outbreak [17, 18, 24].

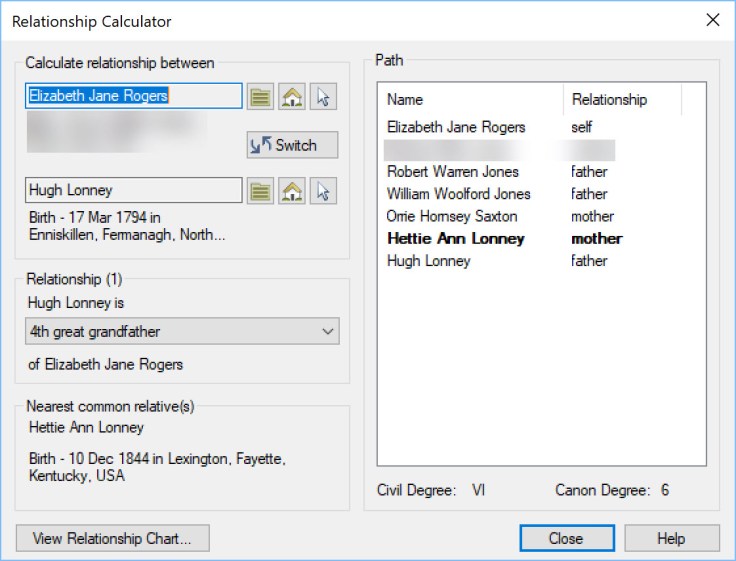

How Are We Related?

Sources

- “Cholera.” World Health Organization, World Health Organization, http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs107/en/.

- “Cholera Plagues: List of the Victims of the Dread Disease in the Epidemics That Swept Lexington in 1833 and 1849”, Lexington, Kentucky, The Lexington Leader, 25 Aug 1901, p. 10, col. 1-4. Information obtained from internet website, < http://www.genealogybank.com/>

- “Enniskillen.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 4 Dec. 2017, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Enniskillen.

- “Germ Theory of Disease.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 25 Nov. 2017, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Germ_theory_of_disease.

- “In the Good Old Days”, Lexington, Kentucky, The Lexington Leader, 10 February 1954, p. 14, col. 1. Information obtained from internet website, < http://www.genealogybank.com/>

- “Inflation Rate between 1833-2017.” Inflation Calculator, FinanceRef/Alioth LLC, http://www.in2013dollars.com/1833-dollars-in-2017.

- “Irish American History to 1845.” Irish American History: Immigration from the 17th Century to 1845., http://www.irish-genealogy-toolkit.com/Irish-American-history.html.

- “Irish-Catholic Immigration.” Teacher Resources, Library of Congress, http://www.loc.gov/teachers/classroommaterials/presentationsandactivities/presentations/immigration/irish2.html.

- “Lexington Cemetery.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 17 Nov. 2017, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lexington_Cemetery.

- “Our Father,” undated typewritten document, in family papers of Robert Warren Jones of Hendersonville, North Carolina; inherited 2013 by his granddaughter Elizabeth Jane Rogers of Anchorage, Alaska; in possession of Elizabeth Rogers. [References to Hugh Lonney as “our father” indicates that this document was created by one of Hugh’s 15 children, the last of whom died in 1910.]

- 1820 United States Census, Household of Hugh Loney, Fayette County, Kentucky; Page 68. National Archives Microfilm M33, Roll 17. [Lists Hugh Loney, white male, age 16-25.]

- 1830 United States Census, Household of Hugh Loney, Lexington, Fayette County, Kentucky; Page 273. National Archives Microfilm M19, Roll 35. [Lists Hugh Loney, white male, age 30-39.]

- 1840 United States Census, Household of Hugh Lonney, Lexington, Fayette County, Kentucky; Page 118. Family History Library Film 0007825, Roll 109. [Lists Hugh Lonney, white male, age 40-49.]

- 1850 United States Census, Household of Hugh Loney, Fayette County, Kentucky; Enumeration District 1; Sheet 124B. National Archives Microfilm M432, Roll 199. [Lists Hugh Loney, white male, age 56, married, born Ireland.]

- 1860 United States Census, Household of Ham Lonny, Lexington, Fayette County, Kentucky; Page 360. National Archives Microfilm M653, Roll 365. [Lists Ham Lonny, white male, age 70, born Ireland.]

- Allen, James Lane. “King Solomon of Kentucky.” Flute and Violin and Other Kentucky Tales, Harper & Brothers Publishers, 1891, pp. 65–93, http://www.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~kyfayett/solomon.htm.

- Find A Grave <www.findagrave.com>, Record of Hugh Lonney, created by: nk, record added: Oct 20, 2012, Find A Grave Memorial #99262091. [Birth: Mar. 17, 1794; Death: Jan. 18, 1863; Burial: Lexington Cemetery, Lexington, Fayette County, Kentucky, USA]

- Find A Grave <www.findagrave.com>, Record of Nancy Lonney, created by: nk, record added: Oct 20, 2012, Find A Grave Memorial #99262117. [Birth: Mar. 7, 1819; Death: Apr. 15, 1858; Burial: Lexington Cemetery, Lexington, Fayette County, Kentucky, USA]

- Funeral Notice for Mr. Hugh Lonney, dated 1/18/1863, in family papers of Robert Warren Jones of Hendersonville, North Carolina; inherited 2013 by his granddaughter Elizabeth Jane Rogers of Anchorage, Alaska; in possession of Elizabeth Rogers.

- Funeral Notice for Mrs. Nancy Lonney, dated 4/16/1858, in family papers of Robert Warren Jones of Hendersonville, North Carolina; inherited 2013 by his granddaughter Elizabeth Jane Rogers of Anchorage, Alaska; in possession of Elizabeth Rogers.

- Kentucky, Death Records, 1852-1964, Record of Nancy Louney. [Original data obtained from Kentucky Birth, Marriage and Death Records – Microfilm (1852-1910). Microfilm rolls #994027-994058. Kentucky Department for Libraries and Archives, Frankfort, Kentucky. Birth and Death Records: Covington, Lexington, Louisville, and Newport – Microfilm (before 1911). Microfilm rolls #7007125-7007131, 7011804-7011813, 7012974-7013570, 7015456-7015462. Kentucky Department for Libraries and Archives, Frankfort, Kentucky. Kentucky. Vital Statistics Original Death Certificates – Microfilm (1911-1964). Microfilm rolls #7016130-7041803. Kentucky Department for Libraries and Archives, Frankfort, Kentucky.]

- Obituary for Mr. Hugh Lonney, undated clipping from an undated newspaper, in family papers of Robert Warren Jones of Hendersonville, North Carolina; inherited 2013 by his granddaughter Elizabeth Jane Rogers of Anchorage, Alaska; in possession of Elizabeth Rogers. [Likely published in a Lexington, Kentucky newspaper in January 1863]

- Ranck, George Washington. “History of Lexington, Kentucky: Its Early Annals and Recent Progress.” History of Lexington, Kentucky: Its Early Annals and Recent Progress, Robert Clarke & Co., 1872, pp. 325–327, rootsweb.ancestry.com/~kyfayett/cholera1833.htm.

- The Lexington Cemetery Company, Inc. <www.lexcem.qx.net>, Record of Hugh Looney. [Birth: unknown; Death: unknown; Burial: 2/1/1863; Disposition Number: 2697; Internment Location: Section: G; Lot: 41; Part: W1/2.]

Leave a comment